By Bradd Libby

Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash, 2017

This is the first in a new series about the pattern of disruption—a way of explaining how our societies and economies change and evolve, and where they might be heading.

It’s often assumed that ‘disruption’ is a uniquely modern phenomenon. But it’s not. Technology disruptions can be found at the heart of major societal and civilizational upheavals going back to even the earliest human settlements.

At RethinkX, we’ve discovered that the rapid and transformative adoption of new technologies–and with them new ideas, new behaviors and new business models–has followed a repeatable pattern for at least hundreds of years, maybe tens of thousands or even millions.

And it is likely to be a key dynamic, if not the key dynamic, that governs whether the next decade or so will produce unparalleled progress and shared prosperity–solving some of the greatest environmental and social challenges we currently face if we harness its power well–or whether we will slide into an extended period of stagnation and decline if we do not.

Today, we are seeing dramatic changes in both the capabilities and economics of incredibly powerful technologies with the potential to profoundly transform the most important sectors of society: how we obtain, store and use energy; how we move ourselves and our goods around; how we get food; which materials we use; and how we communicate with each other.

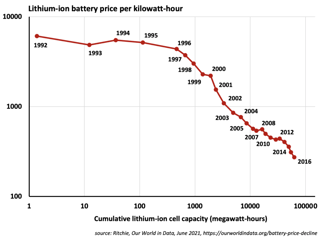

Many of the key transformations have been under way for several decades, in areas like solar photovoltaics, wind power and lithium-ion batteries, precision fermentation and cellular agriculture, along with astounding improvements in communications, data storage, digital photography and artificial intelligence that are driving a revolution in autonomous electric vehicles. And all these revolutions are not happening in separate silos, but simultaneously, together, in a way which is enabling each other.

Where might these disruptions lead? How long might they take? And what might they mean for the very nature and structure of our societies and economies? Answering these questions might seem like gazing into a crystal ball, but when you realise that we have experienced many, many disruptions before, we don’t need a crystal ball. We just need to understand the pattern of disruption.

To help you make sense of the future of transportation, agriculture, materials, energy and communications, we need to take you into the past. As RethinkX’s Dr. Adam Dorr explained in 2021 on the eve of COP26:

'We live lives our ancestors 10,000 years ago couldn’t begin to imagine and their most pressing problems are trivial to us. And the only difference between us and them is that we have better tools…'

'Disruptions are unintuitive. They tend to sneak up on us and then suddenly they unfold much, much faster than we expect. In just a decade or two, for technologies of all kinds, we see the same pattern of disruption again and again throughout history. And disruptions do more than just swap a new technology in for an old one. Electricity wasn’t just cheaper whale oil. Automobiles weren’t just faster horses. Farming wasn’t just more fruitful hunting and gathering. These better tools transformed energy, transportation, and food and civilization along with them.'

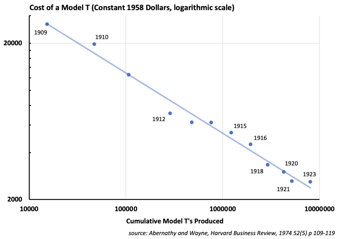

By closely studying economies and societies that have gone before us, we are able to see something truly astounding: the occurrence and reoccurrence of the same fundamental pattern of disruption. Time and again, a new technology is developed that improves in capabilities and decreases in costs, the more of it we make. This happened a century ago with the Model T and has been happening recently with the lithium-ion batteries that are now, once again, revolutionizing the transport industry.

|

|

So how does this pattern work? As costs decline and performance improves, the new technology becomes better and cheaper at meeting an important need or demand in society. The new technology reaches a take-off point, after which it quickly displaces the old technology. During this process, the new technology grows in an S-shaped profile, and the old one declines in an S-shaped profile, overlapping each other to form a graph that looks like the letter X. Just as with finding treasure, here X marks disruption.

We saw this pattern, for instance, with ‘yellow dent’ hybrid corn becoming the dominant strain in the U.S. in the 1930s and 1940s, and then again with genetically modified (GMO) corn replacing non-GMO strains in the early 2000s.

But the crucial issue is that the new technology is not just a replacement for the old one. Instead, the new technology expands the total market. In this case, we grow much more corn in the U.S. today than we did last century: so much corn that cheap high fructose corn syrup displaced cane sugar in Coca-Cola and Pepsi over just a few years in the US during the 1980s. Cheap corn-derived ethanol then went from being relatively rare to relatively common in U.S. automobile fuel, again in an S-shaped profile, over about fifteen years starting in the early 2000s.

Frequently–but not always–the disruption unfolds over an extremely short period of time, just 15 years or even less.

Here are three examples from the last century. By 1945, nylon, which was introduced in 1938, had almost completely replaced silk (which itself had undergone a revolution in worm breeds over just a decade or so earlier in the century). Synthetic rubber, again due to the war, went from 0% of the market in 1941 to more than 80% by 1944. Televisions, which were in less than 10% of U.S. homes in 1950 were in more than 80% of homes just eight years later.

In materials and agriculture, we have repeatedly seen synthetic products replacing ones derived from plants, like artificial red fabric dyes disrupting natural ones in the 1870s, or artificial indigo dye replacing natural indigo in the 1890s.

Likewise, in the past couple of decades, the U.S. market has seen cheap synthetic opioids (like fentanyl) disrupt heroin; while cheap synthetic methamphetamines (from phenyl-2-propanone) have disrupted pseudoephedrine-derived meth.

These disruptions often play out faster than expected, in part because the new technology not only gets better and cheaper, but by the same token the old one gets worse and more expensive.

Particularly in capital-intensive industries, as customers leave the old technology for the new one, manufacturers stop development of the old products. As servicing and maintaining the old technology becomes more difficult, a shrinking pool of die-hard users are forced to support the old industry’s business operations, resulting in a loss of economies of scale.

These dynamics have played out across all manner of different products in entirely distinct industries: from ballpoint pens to birth control pills, from vaccines to videotape, and from planes to photography.

We have seen disruptions in both military and civilian technologies, from the size of the U.S. nuclear warhead fleet growing dramatically over the late 1950s and 1960s, to nuclear power becoming the dominant source of electricity in the 1970s and 1980s in France.

But we know that the pattern of disruption is not exclusive to modern life–because we have seen the X-curve even tens of thousands of years ago, as Homo sapiens replaced the Neanderthals. This is not just an analogy–in a recent computer simulation study published in Quaternary Science Review, Dr. Axel Timmermann of Pusan National University in South Korea found that the Homo sapiens population of central Europe replaced (and exceeded) the Neanderthal population in a manner consistent with observed empirical data if we were several times better at competing for food than them.

One of the most profound lessons from studying the pattern of disruption is that disruptions are rarely if ever only about technology. All the disruptions mentioned here had enormous social implications, both intended and unintended.

With this new series, we will throw light on both the pattern of disruption itself, and the tremendous but often poorly recognised consequences of that pattern, including:

How powerful self-reinforcing feedback loops drive many new technologies to become dramatically cheaper in cost and better in capabilities, in turn driving incumbent systems to deteriorate and revolutionizing how markets work, often in a very short period of time.

How better technologies and business models have profoundly reshaped how we live our lives in numerous social and cultural contexts, and will continue to reshape them in the near future with enormous implications on the personal finances and personal wellbeing of those who understand these dynamics.

How some of the most profound social, geopolitical and ecological changes have arisen from technology-driven disruptions, often unintentionally and in unexpected ways.

How technology-driven disruptions unfolding right now will continue to have enormous and unpredictable social, geopolitical and ecological implications in the future, which we can, however, be in the best position to anticipate when we truly begin to understand the pattern of disruption.

Technological disruption is a motor of history, yet it still remains poorly understood. By understanding the pattern of disruption, we will be able to shed light on some of the core dynamics that define human existence: we will better understand where we have come from as a species, and be better equipped to recognise where we might be heading, and the choices available to us on our way there.

Over the course of this series, we will invite you to participate in what we do every day at RethinkX: to Rethink Everything.

===

In Part 2 of ‘The Pattern of Disruption’, we will look at how quickly disruptions can unfold, when necessity requires, even with radically new technologies.