“Stealing a man’s wife, that’s nothing, but stealing his car, that’s larceny.”

Americans love their cars. They have done since the first Model T Ford rolled off the production line back in 1908. By the mid-20s, more than 20 million were registered in the U.S.. But it wasn’t until after the Great Depression and World War II that the golden age of the U.S. automobile was born.

A powerful symbol of the nation’s post-war freedom and renewed confidence, cars became ever more flamboyant, powerful and glamorous. Iconic brands such as Cadillac, Chevrolet, Mercury, Lincoln and Buik designed some of the most recognisable and evocative cars ever made, stirring the passions of kids and inspiring the dreams of motorheads across the nation. Learning to drive became an essential rite of passage for teenagers, a prelude to a youth spent cruising the streets and, for many, customising and modding cars for decades to come. Driving had become the ultimate expression of freedom, individuality and personal empowerment.

We hear this a lot at RethinkX. Or rather the distilled version–that people are simply too attached to their cars to give them up in favour of an autonomous, ride-hailing service. It’s the aspect of our research that people seem to struggle with the most.

But are people as attached as some seem to think? Is the allure of driving as powerful as it once was? A raft of recent research suggests not.

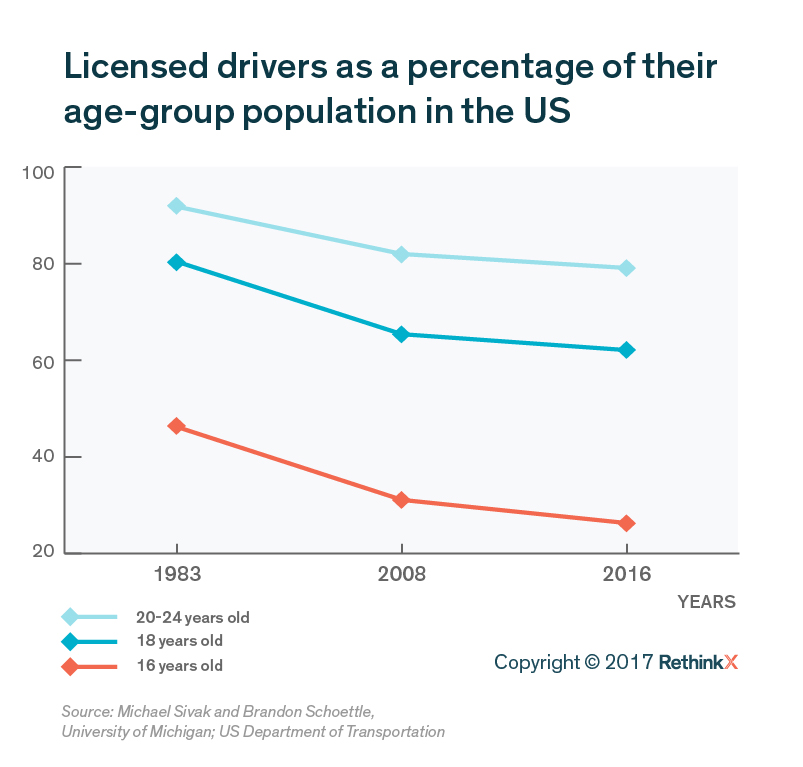

In 1983, almost half of 16 year olds in the U.S. had a driver’s license. In 2016, little more than a quarter did. Similar declines can be seen among other young age groups (see chart below), despite a slight uptick in the last year. And there’s no evidence to suggest people are just delaying their driving test.

In the U.K., research commissioned by the government has shown that in 1992-1994, 48% of 17 to 20 year olds held a license (you cannot drive in the UK till you’re 17). By 2014, the figure had fallen to 29%, a huge drop in just 20 years. The equivalent figures for 21 to 29 year-olds are 75% down to 63%.

Indeed, separate government figures show that 386,000 driving tests were taken by 17 year olds between April 2007 and March 2008. By 2016-2017, the number had fallen by a quarter to just 295,000. For 18 year olds, the number was down 10%.

Other studies have shown similarly declining rates in Australia, Norway and Sweden, with more modest falls in Japan and Germany.

The causes of the decline are numerous. The U.S. study was preceded by a survey from the same team of academics. The top three reasons given for not driving were “too busy or not enough time to get a license,” “owning and maintaining a vehicle is too expensive,” and “able to get transport from others.” In other words, driving is no longer a priority for younger people, particularly as alternatives are increasingly available. Indeed, the survey found that 22% of respondents had no intention of ever getting a licence.

There are more specific reasons why this should be the case. Young adults are spending far more on housing than previous generations, leaving less cash to buy a car, while urbanization has increased both the cost of car ownership and access to on-demand alternatives. Other reasons may be harder to quantify, but include increased participation in higher education, the growing popularity of working from home and increasing environmental awareness.

We believe the reason people will happily give up their cars and move to what we call Transport-as-a-Service (TaaS)–effectively an Uber-style, robotaxi–is economics.

TaaS will cost about 15 cents a mile, compared with 80 cents for buying a new gasoline car or 38 cents for one you already own. In other words, TaaS will cost less than half what it costs to keep your existing car running.

When you consider that more than half of Americans have less than $1,000 in the bank, saving $5,600 a year–which is what this differential per mile equates to for the average U.S. family–is pretty compelling.

But as the growing body of recent evidence suggests, the resistance to this move will not be as strong as some think. In fact, the move away from car ownership may have started already–almost 10% of Americans who sold their cars last year didn’t buy a new one.

As hard as it may be to accept for those who hark back to a more innocent age – the golden age for the American automobile–younger people today just aren’t that into cars.